Monday, 27 October 2008

The Importance of First Aid Knowledge in Every Soldiers and Officers.

THE IMPORTANCE OF FIRST AID IN EVERY

SOLDIERS AND OFFICERS.

If all my men had known the basics of life-saving first-aid knowledge, one of my men’s life could have been saved that one fateful night. He had accidentally shot himself in the thigh. It was just a mere flesh wound but because none of his friends and platoon commander knew how to apply the first-aid treatment to stop the bleeding, the poor soldier died on the way to a rendezvous some 15 map squares away (about 15 kilometers)!

It was a most regrettable incident, which happened at the wrong place and at the wrong time.

My Company of 3rd Rangers was given a sector in the most difficult area in the Kinta District of Perak. As usual, I broke up the Company into three groups so that I could effectively search my area of responsibility. Each of the groups made their own way to their sub-sectors right from the debussing point. By about 5 pm, they stopped for the night and started to make their overnight base. With a parang in one hand and his M16 in the other, this soldier went to cut some wood for his basha. He tripped and his M16 went off. He was shot in the thigh.

I was frantically trying to get a helicopter to evacuate him before last light but failed. Night flying was impossible as there was not enough light for the helicopter to fly in.

I was, at that time about 10 map squares (about 10 kilometers) from the platoon. For me to move and meet up with them was like looking for a football 10 kilometers away. It was made more impossible at night. What else could I do but to tell the platoon to wait for daylight the next day and meantime to treat the wounded soldier with first-aid as best as they could!

By about 9 or 10 p.m. that night, the platoon commander radioed me – the soldier’s condition was deteriorating and they had to bring him out on a stretcher to the nearest motorable track which was about 15 map squares away! So, armed with torch lights and machettes, they carried the poor soldier through the mountainous jungle in the pitch-dark night. It was no easy task and needed their sheer determination. It was a whole night move and by the time they reached the rendezvous, the poor soldier was dead. He had lost too much blood!

The question that had always haunted me was: could his life be saved if his comrades knew how to apply and administer the right first-aid without having to move him 15 kilometers through the difficult terrain in the pitch-dark night?

I think, this was a classic example of the importance of first-aid. Every soldier must know how to treat all common sicknesses, fractures and wounds suffered in battles or in operational areas. It should be a must, if we want to avoid unnecessary loss of lives. First-aid knowledge must be made compulsory to all soldiers and officers. It should be incorporated into rank promotion examinations.

My Field Leadership Style.

MY FIELD LEADERSHIP STYLE.

The subject of leadership is a well-exhausted topic of discussion. Yet, every new writings and discussions on it are far from boring.

Every commander has his own brand of leadership. There is no fixed brand of leadership for any particular level of command and scenario. The rule of the thumb is - if the commander succeeds in whatever task he is set to undertake, then, his style of leadership is the right concoction for the occasion – regardless how unorthodox his style may seemed.

Sections and platoons are the most forward troops in the front line. They are always the first to be in contact with the enemy. Invariably, they will be the first to notch a success or the first to suffer casualties. In other words, they are always in danger. They must always be alert and never let their guards down. In fact, they should always be one-up on the enemy. They must maintain the initiative. They can do all these if the commander has the capability, the physical and mental strength, the courage and the stamina to ensure they maintain the initiative.

In my many experiences and contacts with the CTs, I had found that not all soldiers were brave and willing to risk his life. You may call them cowards if you will. This is a natural human tendency. It is only natural for him to keep himself alive – he has a wife and children to think of and the only sure way of ensuring he is alive is by not doing anything and simply not putting their heads on the chopping boards! Given the slightest chance, this group of soldiers will simply ignore your commands! Just imagine soldiers who refuse to obey and execute orders in the battle fields! I don’t want to think of it. The consequences would be catastrophic!

I was fully aware of this shortcoming. I strongly believe this shortcoming can be overcome by the commanders themselves. They have to show that they are courageous and unafraid to face the enemies. They must move well forward, show their presence and courage at all time. These characteristic will rub and infect the soldiers.

My motto was always TO LEAD BY EXAMPLE and WHAT THE SOLDIERS CAN DO, I CAN DO BETTER.

In due time, trust in one another is built. Camaderie and espirit-de-corps will grow. These are the most important ingredients for a successful unit.

In the absence of the real challenges from the real enemies, other means must be found to inject and build up these all-important qualities into every soldiers and officers. Without these qualities, soldiers and officers will just be an unthinking and unenthusiastic robot. The unit will be a unit without any soul.

Friday, 17 October 2008

Books For Sale

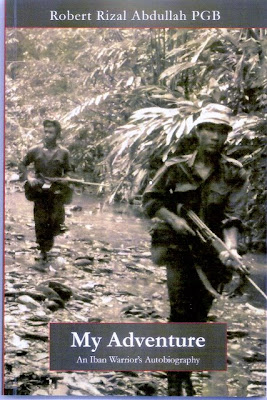

AN AMAZING ADVENTURES OF A MODERN IBAN WARRIOR AND A POET.

Born into an Iban family in a remote long house in Sarawak, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Rizal Abdullah PGB@ Robert Madang Langi was destined to be a modern Iban warrior.

His whole life was an amazing adventure that is unthinkable and a nightmare to most, even today.

His determination, courage and prowess in the battlefields were the very characteristics that made the Ibans warriors second to none. These were the qualities that had made them stood out from the rest.

His autobiography MY ADVENTURE tells about his courageous and amazing adventures in his young life and how he finally joined the Malaysian Rangers and fought the communist terrorists (CTs) in Sarawak and Malaya in the 70s and 80s. For his role in an attack on a CT camp in Sarawak in 1973, he was awarded the nation’s second highest bravery award – the Panglima Gagah Berani (PGB).

He has an ardent interest in poetry writing. In his second book, an anthology, REFLECTIONS OF A SARAWAK POET, AN OFFICER AND A GENTLEMAN, he has written a collection of poems about his nostalgic life in the long house, his former school, Tanjong Lobang School in Miri, Sarawak, some aspects of his military career and life in general.

RM39.00

Capture of 2 CTs in Kanowit

The Capture of 2 CTs in Kanowit

I was "hand picked" by the Commanding Officer of 10th Rangers, Lt Col M F Nesaratnam, to be his Second-In-Command. He was an old buddy when we were in 3rd Rangers in the late 60s and early 70s when 3rd Rangers was based in Taiping, Perak.

Soon after graduating from the Armed Forces Staff College, Haigate, Kuala Lumpur at the end of 1982, I immediately reported to 10th Rangers in Bau. It was an appointment I looked forward to, for many reasons. Firstly, I was going to have a good working relationship with the Commanding Officer as he was not only a close buddy but we shared many common interests - one of them being the game of squash. Our quarters in Penrissen camp were within shouting distance and we often played endless hours of entertaining squash.

The late Lt Col Nesa was an outstanding and a natural sportsman. He especially excelled in racquets games - tennis, badminton and squash. I was good myself but however hard I tried, I could never beat him! How frustrating!

Secondly, I was going home! I missed my folks and my long house. The posting would give me the golden opportunity to catch up with many many lost years. My long house was only two hours drive from Kuching and I hoped to take full advantage of it whenever time would permit.

I remembered in early 1983, Rejang Security Command (RASCOM) intensified its effort, through Operation Jala Aman, to eliminate remnants of the hardcore CTs in the Third Division of Sarawak. A cordon and search operation was mounted on a group of CTs. All available troops, including Service units, were called in to assist. There had been a number of contacts and firefights but the Security Forces failed to inflict casualties on the elusive CTs. Surprisingly, they managed to slip through the tight cordon. When all these were happening, I was at our rear base in Bau, a small town some twenty kilometers from Kuching, the capital city of Sarawak.

One day, I received a message from RASCOM in Sibu, asking me to report for a special mission. I was to lead three clandestine groups of one each from 8 Rangers, 10 Rangers and a Police Special Branch Unit in an operation code named Jala Aman 3 in Bawan, Pedai and Bob areas along the Rejang River, just below Kanowit. The Chinese in these areas were known to sympathise and support the CTs. After all, many of them were related. After Operation Jala Aman 1 and 2, it was thought that the CTs might try to contact their supporters and

sympathizers in these areas.

On July 23, 1983, disguised as Police Field Force escorts for a Police Special Branch team conducting masses works in the area, we took to familiarise ourselves with the area and identify the target houses. We were dressed in their jungle green uniforms. This phase lasted one whole day. We returned to Sibu with the Police team late that evening. A couple of days later, under cover of darkness, we came back to the same area. This time we were disguised as locals. For the next two weeks, optimising and taking advantage of my night vision goggle, I patrolled and laid ambushes at night. By day, I observed the target houses and the surrounding areas.

It was a disappointment. The CTs were nowhere to be seen and there was no movement at all. The Chinese in that area must have smelled the operation and left.

On August 7, 1983, I was pulled out to Kanowit town. The other two teams followed suit a few days later.

Three days later, acting on a sighting information from the Special Branch, I was redeployed to an area sandwiched by two tributaries of the Rejang River - Pelak and Jih. Reinforced by twelve SBPU personnels, I searched the area for three days. Again, the result was negative. On August 14, 1983, we were withdrawn again to Kanowit.

Troops in other sectors of operations were also being pulled out. It was a clear sign that Operation Jala Aman 3 was drawing to a close. It was going to be a disappointment and another failure!

Barely two hours after our arrival in Kanowit, I was told to meet two senior staff officers from RASCOM, Lieutenant Colonel James Tomlow ak Isa and Superintendent Lawrence Lim in Kanowit Police Operation Room. They were accompanied by two Border Scouts –both were former soldiers of the elite 1st Rangers, the direct descendent of the famous and illustrious Sarawak Rangers. They looked happy and excited and I knew they must be having good and reliable information. My guess was right.

According to a long house headman in Machan, Kanowit, he had been trying to persuade two CTs (a couple) to surrender to the authority. They had been staying in his farm for the past two days. The CTs refused but instead had asked the headman to bring them to Kanowit town in his long boat. They were to leave Machan for Kanowit at dawn on August 15, 1983, and expected to reach Kanowit town between 7.00 a.m to 8.00 a.m on the same day. A waiting car would bring them to Sungai Nibong, a place further down the Rejang River and from there to an undisclosed destination. In order for the car driver to recognise them, the male CT would be wearing a red cap.

The plan was for me to intercept them as soon as they land at any of the jetties immediately below the main jetty of Kanowit town. Firing of firearms must be the last resort in order to avoid accidental shooting of civilians; who by then would be up and about their daily chores.

The operation involved a total of nineteen personnel from the SBPU team, the famed Border Scouts and my special group of five from 10th Rangers. We were divided into three groups. The first group of six SBPU personnel would be deployed to observe and follow the CTs from Machan. Halfway down, another group of six SBPU personnel would be deployed as a cut off at a place called Balingan/Melipis. I and my group, including the two Border Scout personnel I met in the Police Operation Room were to apprehend the CTs as soon as they land in Kanowit.

The two groups for Machan and Melipis were deployed at about 2.00 a.m on the day concerned. I moved into my position at about 6.00 a.m. I didn’t want to move in too early and aroused suspicion of civilians moving about in the area.

There were three possible landing points – three small jetties that spanned an area about one hundred meters wide and only fifty to sixty meters from the rows of shop houses overlooking the river. I deployed my men to cover all three jetties. I were to observe the jetty in the centre together with the two Border Scouts as they were able to recognise the long house headman driving the boat from Machan.

Dressed in civilian clothes and with our weapons hidden but within easy reach in the bushes, we blended with the locals, who by then were already busy going about their chores. We waited and scanned every boat that came down the Katibas river.

After so many boats and dented hopes, we noticed a small long boat with three people in it, slowly coming down the river. The person in the centre was wearing a red cap! The Border Scout confirmed the driver of the boat was the long house headman. We retrieved our weapons and crouched low behind the bushes.

The boat went pass the three jetties. I thought for a moment, they were trying to avoid the town and went further downriver. I quickly made up my mind on what I would do if that was the situation. But then; it made a wide U-turn and headed for my jetty. As it came alongside, I and the two Border Scouts were already there to ensure there was no way the CTs could escape from us alive. Almost at the same time, the SBPU groups from Machan and Melipis also landed at the jetty. They had been tailing the CTs all the way.

We relieved the CTs of their belongings and took them into a waiting police vehicle. They were taken to Kanowit Police Station, where Suprintendent Lawrence Lim and Lieutenant Colonel James Tomlow were waiting. To RASCOM, the capture of the two CTs was a huge success as they would be able to shade lights on so many things that all these while had been purely intelligent guess works. For me that was a befitting end of my involvement in Operation Jala Aman 3. A couple of days later, I and my men returned to our home base in Bau, Sarawak. For that little episode, my commanding officer presented me with a dagger inscribed with the words “For the capture of 2 CTs in Kanowit on October 15, 1983.”

That little episode marked the beginning of my adventure and the wild-goose chase with remnants of the CTs in the Third Division of Sarawak throughout the 1983 to 1987 period.

My Team that captured the 2 CTs in Kanowit comprising of

SBPU, Border Scouts and a Special Team from 10th Rangers.

I'm 7th standing from the left.

Thursday, 16 October 2008

Canoeing Down Sabah's Second Longest River (Segama River)

Canoeing Down Sabah's Second Longest River

(Segama River)

Rivers had always been a part of my life. It had been a source of fun. We depended on it for our living. Many-a-time, it almost took my life. Because of these, I had great respect for rivers.Towards the end of 1978, we received the good news from Headquarters 5 Infantry Brigade based in Kota Kinabalu. Units were encouraged to carry out “adventure training” within their area of responsibility. Unlike Malaya and Sarawak, Sabah had always enjoyed comparative peace, except for the sporadic raids by pirates along its Eastern coasts and islands.

When the news came, my first thought was on white-water canoeing. Water, somehow, had always been a part of my life. I was no stranger to riverine adventures. I had crossed the mighty Rejang in a makeshift canoe when I was seven years old. I had capsized in the middle of Kamena River. I had conquered the treacherous rapids of Perak River in a dug-out canoe! Today, with the availability of kayaks, it was an unthinkable idea to shoot the rapids in dug-out canoes! After what I had gone through, I was naturally inclined towards yet another riverine adventure.

I made a map reconnaissance. Segama River seemed the most likely river that could offer the challenges I was looking for. However, I needed to have a closer look at the condition and situation along the whole length of the river. A week later I had my request for an air reconnaissance granted. A Royal Malaysian Air Force Allouette helicopter took me and my Second-In-Command, Lieutenant Mohd Saad to have a closer look at the river. The sea and the river mouth were misty. Strong winds were whipping up the waves frenzy. It was the usual rough weather at this time of the year. It was monsoon season - the time of the year when fishermen were forced to stay home and mend their fishing nets. There was little else they could do, anyway.

The sea was too rough for their small boats. As we flew inland, the milky-coloured river twisted and turned through the seemingly flat and thickly forested lowland. This was the sanctuary of the pygmy elephants, monkeys and many other protected species of wildlife. We flew past the town of Lahad Datu and could see the point where the Lahad Datu – Sandakan trunk road was severed by the Segama River. An old-fashioned ferry pulled by steel cables was the only mean of transporting vehicles and people to and from the opposite banks.

From here on, the terrain rose sharply into the mountainous interior. And for the first time I saw white water as the river went through narrow gorges and steep gradient. That was the sort of river I was looking for. Unfortunately, we couldn’t find any motorable tracks that we could use to carry our rubber dinghies and equipment to where the rapids were. Neither could we find any suitable helicopter landing point. It was apparent that our adventure down the Segama River would have to begin from the ferry point, a distance of more than 100 kilometers to the coast.

The number of personnel I could take on the adventure training depended on the number of dinghies available in the Battalion Assault Pioneer platoon. There were only five good dinghies – one small, two medium and two large, each could comfortably accommodate two, four and five people respectively. I could only take twenty men. I wanted to be fair and asked for volunteers who could swim and didn’t have any phobia of water.

We spent the next few days on maintenance. Over years of neglect and never being used, the dinghies were in dire need of maintenance – pin-hole punctures had to be patched, missing ropes replaced and loose screws tightened. The dinghies were mouldy and had to be scrubbed and dried under the sun. We knew the inflatable rubber dinghies would be prone to punctures and ensured we bring enough repair kits, as it would be impossible to find them along the river. We couldn’t take any chances.

December 1, 1978.

I had given myself ten days to complete the journey to the coast. It was a misjudgment. Despite the slow current and the absence of rapids, we were to complete the journey in only five days.

After two weeks of preparations, twenty of us, all volunteers, left for our staging camp in Lahad Datu on December 1, 1978. The whole country was still under the spell of the monsoon season. The main trunk road from Tawau to Sandakan and Kota Kinabalu was still under construction. It was dusty in dry weather and muddy and slippery when wet. It took us five hours to reach Lahad Datu camp.

December 2, 1978 – Day 1.

We wanted to start the day early and were at the ferry crossing point at 8.00 a.m. Curious onlookers were beginning to gather around us as we assembled and inflated our dinghies. By 9.00 a.m., we were on our way to discover and unravel the secrets of Segama River.

We were caught unprepared by what we were about to face. Climax of the monsoon season had passed. The swollen river was subsiding, but still well above its normal level. The water was murky and I realised we would have problem finding clean water for drinking and cooking. Notice the ferry in the background.

We were caught unprepared by what we were about to face. Climax of the monsoon season had passed. The swollen river was subsiding, but still well above its normal level. The water was murky and I realised we would have problem finding clean water for drinking and cooking. Notice the ferry in the background.

At this time the monsoon season was subsiding. But the aftermath and havoc it created is what you see in the picture - murky water and mud on the river banks. However, the problem was not that acute. We could find acceptably clean water in the tributaries of Segama River. It would be perfectly safe for drinking, after boiling. We had gone through worse situation before. A couple of villages along the river were supplied with piped water where we could fill up our water containers.

The weather was really hot. We tried to erect some form of shades on our dinghies and use whatever head gears we could lay our hands on.

After about five kilometers and with no sign of let-up, we decided to stop to erect make-shift shelters on our dinghies. They looked undignified but provided us the protection from the sun. We didn’t want to be like over-cooked lobsters too soon as we had a long way to go.

Being the first day, we didn’t want to exert ourselves too much. After all, we didn’t have any dateline to meet and could take all the time in the world. I wanted to enjoy every inch and every minute of the journey. At 3.00 p.m. and after covering thirteen kilometers, we made a night stop by the river bank. That evening, we soaked ourselves in the cool comfort of Segama River. It was like a tonic. I could feel my energy and spirit seeping back into my hot and tired body. Tired after about five hours of rowing and the thought of another full day tomorrow, we hit our hammocks by 8.00 p.m.and lulled into sleep by the cacophonies of the cicadas, crickets and nocturnal birds.

I took a cool bath in a small tributary where the water was less muddy. I didn't want to swim because the bottom of the stream was muddy.

The light dawn drizzle kept us a little longer in our hammocks. Breakfast was a speedy affair. We cooked instant noodles and washed it down with tea. It was over within ten minutes

.

This was a typical scene when we had our meals by the river banks.

I'm in the centre in white T shirt.

I'm in the centre in white T shirt.

At approximately 7.30 a.m., we continued our journey down the Segama. The welcomed drizzles followed us most of the way. It helped to cool us down. It provided a welcome relief from the sweltering heat.

At approximately 7.30 a.m., we continued our journey down the Segama. The welcomed drizzles followed us most of the way. It helped to cool us down. It provided a welcome relief from the sweltering heat. The river was becoming noticeably broader by the hour. Its colour, however, remained milky - indication of logging activities in the interior. Strange though, there were no signs of wildlife – not even monkeys and birds. We had lunch by the river bank and at 4.00 p.m., decided to stop for the night.

December 4, 1978 – Day 3.

We woke up to loud croaking of frogs and chirpings of birds as they heralded-in a hot fine day. Spears of sunlight pierced through the thick morning mist. Giant trees towered above us. A number of gibbons were jumping from branches to branches high above us – unperturbed and perhaps unaware of our presence.

This rock was said to have been bombed by the Japanese troops, possibly to allow their patrol vessels to go deeper inland.

This rock was said to have been bombed by the Japanese troops, possibly to allow their patrol vessels to go deeper inland. December 5, 1978 – Day 4.

We had passed the pygmy elephant sanctuary but didn’t have the luck to see the elephant. I noticed two small leaks in my dinghy. However, they were nothing to worry about. As usual, we stopped for lunch at 12 noon and I took the opportunity to patch up the leaks. At 3 p.m, after about 17 km, we reached a village called Tomanggong Kecil. I decided to stop there for the day and carry out checks and maintenance on our dinghies, which had been in the water for four days.

December 6, 1978 – Day 5.

The monsoon rain came down with vengeance at about 3 a.m. when we were still fast asleep. We were awakened by claps of thunder and strong gusts of wind which blew cold drops of rain onto our faces. Despite having an interrupted sleep that night, we kept our schedule and left Tomanggong Kecil at 7.40 a.m. The river was a little swollen after the night’s heavy downpour. We reached Kampong Tidong at 1 p.m. It was the last village along the Segama River and closest to the Sulu Sea on the North Eastern coast of Sabah.

We stopped at a jetty, tied our dinghies and climbed up onto dry land. The village was made up of a number of typical, Malay-like houses. This was the home of the Tidong clan. Talking to them was easy as they spoke the Malay language. They were friendly and were quick to offer us any assistance we required. That evening, we invited the village headman, Pak Cik Ahmad and a young man called Ghani to share our dinner of Army ration and some fresh fish we had caught on the way down. They were very pleased to accept our invitation. We were the first group of soldiers that had visited their village since World War 2!

The next day, I and my Company Second-In-Command, Lieutenant Saad, went down to the mouth of Segama River in Ghani’s boat, which was powered by a five horse-power outboard engine. We provided the petrol. Besides looking at the possibility of continuing and ending our journey on the coast, we also wanted to earmark a suitable location for a helicopter landing point where it could pick us up. Looking at the speed of the incoming tide, I knew it was impossible for us to go against it and get down to the coast.

I didn’t want to take the risk of being swept out into the sea by the strong current. Furthermore, the lack of fresh water was another deriding factor that prompted me to decide and end the journey at Kampong Tidong.

Ghani, our boatman, was the son of the village Headman. He wouldn't accept any money I wanted to give him for a whole day's job. He just wanted us to provide the petrol.

Ghani, our boatman, was the son of the village Headman. He wouldn't accept any money I wanted to give him for a whole day's job. He just wanted us to provide the petrol. During this time, the Tidongs were prisoners in their own village. On the return journey, we stopped by a deserted logging camp. Logging activities had also been put on hold, waiting for the fury of the monsoon season to tide over. Despite being on a patch of dry land, there was no suitable place that we could use as a helicopter landing point. Both sides of the river were mangroves swamps. We were disappointed and returned to the village. The village didn’t have any open field and the only suitable landing point was an area with several big trees, not far from the village. After obtaining permission from the village headman to use the location and cut down the trees, we set down to clear the area with the help of the villagers. It was hard work and took us several days. It was a good thing we had ample time as we were five days ahead of schedule.

The day finally came for us to say farewell to the Tidongs. As our Nuri helicopter took off vertically to clear the tall surrounding trees, we could see their faces, wearing looks with a thousand messages. We wondered whether we’d cross each other’s path again. We knew it would be very unlikely. Our two years operational tour of duty in Sabah was due to end very soon. We were returning to Peninsula Malaysia. Before we knew it, our two years in Tawau, Sabah drew to a close. At the end of 1979, just when we were getting used to the pace of life there, 3rd Battalion the Malaysian Rangers packed up again. This time we were moving to Terendak Camp in Malacca – a beautiful camp facing the Straits of Malacca.

The day finally came for us to say farewell to the Tidongs. As our Nuri helicopter took off vertically to clear the tall surrounding trees, we could see their faces, wearing looks with a thousand messages. We wondered whether we’d cross each other’s path again. We knew it would be very unlikely. Our two years operational tour of duty in Sabah was due to end very soon. We were returning to Peninsula Malaysia. Before we knew it, our two years in Tawau, Sabah drew to a close. At the end of 1979, just when we were getting used to the pace of life there, 3rd Battalion the Malaysian Rangers packed up again. This time we were moving to Terendak Camp in Malacca – a beautiful camp facing the Straits of Malacca.

Monday, 13 October 2008

Operation Jelaku 6 - The Final Blow. Part 3 A Dawn Attack on the CT Camp.

Operation Jelaku 6

The Final Blow

Part 3- A Dawn Attack on the CT Camp

(to be read with part 1 & 2)

I divided my men into two groups – the seven-men assault group under my command and the eight-men cut-off group under the command of my Sergeant Major, WO 2 Norizan Bakri. My plan was simple. The cut-off group was to be in position early that night, some fifty or sixty metres behind the enemy camp, to cut off their withdrawal route when I launched the attack.The assault group was to be in position one or two hours prior to H hour at 6.30 a.m on October 11, 1973 - just about five hours away. We were to be in pairs and spaced out between five to ten metres apart. Alternatively, just in case the CTs would break camp much earlier than anticipated, the signal to attack would be the sound of any firing from whichever group that noticed it.

At about 2.30 a.m, the cut-off group, under cover of the torrential down pour, moved slowly and cautiously to their positions. I was told later, in the pitch darkness, they had bumped more than once into the CTs' bashas. I didn’t want the assault group to move in at the same time as it was still too early. We needed the few hours to rest and get some sleep. Hopefully, we were able to recover from our fatique, before the big task ahead.

We took shelter from the merciless rain under a makeshift ponco we had erected in between the buttress roots of a giant tree. Soaked to the skin and chilled to the bones, we huddled closed together, in order to get some warmth into our shivering bodies.

I told the men to catch some sleep, if they could. But I doubt if any of us were able to do so. With a battle coming up in just a few hours away, and the enemy just a stone –throw in front of us, who in their right sense of mind could?

We were excited, enthusiastic and raring to go. After what we had gone through and worked at, we didn’t want to botch it up and threw away this once-in-a lifetime golden opportunity! At 3.30 a.m, the rain had fizzled down to light drizzles. Then, suddenly, I heard some noises in the direction of the CT camp. Ten minutes later, red lights flickered, glowed and danced in between the foliage – some fifty to sixty metres away. I realised then, the CTs had woken up – possibly getting ready to break camp early and made it to the Sadong River before we did.

What they didn’t know was that we were already on top of them!

They had kindled a bonfire. We found out later, they were actually cooking breakfast and drying out their wet clothes over the fire. With the CTs already awake and the rain that had fizzled down to light drizzles, I realised our task of moving into our assaulting positions would be more difficult to conceal. The sight of the bonfire and the dying drizzles prompted me to change my plan. I decided to move in immediately before the rain stopped completely. At least, the drizzles would conceal the sounds we would be making when we moved.

That thirty metres was the longest and most difficult thirty metres I had ever gone through all my life. We were up to our shins, at times up to our knees in the swamp. Each step had to be taken carefully in order to avoid the sucking and squelching noises the mud and marshy ground were making. Each step had to be slowly cleared of leaves and twigs. Each step had to be retracted slowly and carefully from the swamp. As if those problems weren’t enough, mosquitoes attacked us in swarms. As minutes ticked slowly by, the heat from the sun was beginning to be felt. Or was it the adrenaline rush?

About forty minutes later, we were in positions. I and my radio operator, Ranger Md Desa were directly in front of the bonfire – some fifteen metres away. In order to get a clearer view, I moved closer to the bonfire, while Ranger Md Desa remained behind a big tree where he hid his radio set. Before I left him, I had pointed out a couple of bashas visible to the right of the fire. He was to attack those bashas when I launched the attack. I would attack the ones to the left.

As I watched the CTs moving around the bonfire, I prepared myself for the coming battle - ensured my magazines of ammunitions were in the right pouches and my webbings were properly secured. I knew, in the heat of battle, I shouldn’t fumble and every second counted.

At 5.30 a.m, I began to notice the pitch dark night was beginning to turn smoky grey. The young saplings and bushes around me began to take shapes. As the light became brighter, I began to feel insecure. I was in the open with little cover from view and practically with no protection from enemy fire. There was nothing I could do about it. I couldn’t move.

My radio operator was about ten yards behind me. The rest of my assault team were strung out to my right. At 6.15 a.m, the sky was clearing. Silhouettes of trees were visible against the dawning sky. The CTs had ceased to move about. I could see only two still remained by the fire. They were ill at ease and must have sensed our presence. They exchanged some words. The silence and inactivity in the camp was most worrying. I sensed they were up to something. Were they about to break camp? Could they had detected our presence and were getting ready for our attack?

All these thoughts went through my mind and they made me worried. I had another fifteen minutes to my H Hour. It was too long and I couldn’t wait much longer. The longer I waited the longer time I would give the CTs time to prepare themselves for our assault. I didn’t want to lose my surprise factor.

Convinced that it was the most opportune time, I launched the assault immediately at 6.15 a.m on October 11, 1973 – five days past my 25th birthday. I grabbed a M 26 grenade, pulled the safety pin out, released the striking lever from my hand, counted three seconds before lobbing it in between trees towards the two CTs near the bonfire. It landed with a splash in a puddle of water to their right. To my horror and dismay, it didn’t explode!

Swiftly, I grabbed my Baretta automatic rifle and released two long bursts at the two CTs who were looking at the direction of the splash the grenade had made. Instantly, all hell broke loose. My radio operator immediately left his tree and charged towards the two bashas I had indicated earlier, shouting out the war cry and with his Baretta spitting fire. I told him not to shout as his voice could indicate his position to the CTs. But in the midst of battle I doubt he could hear me.

The jungle came alive. There were a lot of shouting and screaming in Chinese. My men on my right flank were also firing into the camp. I veered left to follow the sounds of retreating CTs. My cut-off group also fired. Sandwiched, the CTs escaped through the open left flank. Suddenly, amidst the chaos, I heard a couple of unfamiliar bursts of an automatic fire from an unfamiliar weapon – it sounded slower and the pitch was lower. It must have been directed in my direction, because the fire from the muzzle was directly in front of me.

Instinctively, I hesitated and didn’t retaliate! My first thought was of my cut-off group. Could that be their fire? By the time I realised it was not, the sounds of the fleeing CTs were well to my left. I kept up the pressure, firing as I went. As the sounds of the escaping CTs disappeared, I stopped to check my ammunitions. I had used five of my seven magazines. I had to conserve my remaining ammunitions just in case the CTs might want to counter-attack.

As I was taking stock of the situation, I heard approaching footsteps, splashing in the water. I drew my dagger and prepared myself for a hand to hand combat. Somehow, when it was about a couple of metres from me, the footsteps stopped. I crouched low and waited for about five minutes. Satisfied there was no one there, I decided to retrace my footsteps and went back into the camp to take control of the situation and quickly organised an all round defence, just in case the CTs might try to counter attack.

The jungle was filled with acrid white smoke of gun powder. I didn’t notice it before. I met up with my assault team and searched the camp. The camp was actually an overnight camp. There were only makeshift tents made of plastic sheets. Some of the CTs were sleeping on the jungle floor while others were in hammocks. One of the CTs killed died in his hammock.

The way they left the camp showed that they were totally caught by surprise. Blankets were strewn all over the place. They didn’t have the time to pack up their belongings. We recovered about 35 packs and assorted items such as torch lights, Iban parangs (machettes), home-made shot guns and pistols, some ammunitions and even transistor radios. One of the radios was still running a Chinese programme. We found seven CTs dead – four females and three males. One of the astonishing find was a talisman written in Arabic found in the jungle boot of one of the male CTs. He had, presumably, got it when he was in Kalimantan, Indonesia, when the Sarawak Communist Organisation decided to go underground soon after the Brunei Rebellion broke out in December 1962.

For the success, however, we had to pay a price. My radio operator was killed and one of my section commanders was wounded on the head. After locating my radio set, I managed to relay the good news to my commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Philip Lee Khiu Fui, through our Mortar platoon which had established a firing position at the fringe of the swamp. I could visualised the excitement the news would have created at the Battalion, Brigade and Division Headquarters. The next day, I was told to rendezvous with 3rd Brigade Commander, Brigadier General Hassan Hj Salleh and my commanding officer at a clearing which took me a good thirty minutes to reach.

The Brigade Commander wanted to congratulate me personally for having achieved the biggest success for the year. I and Lance Corporal Ahmad Adnan were awarded the nation's second highest gallantry award by the King.

The ripples of excitement were felt as far as the Armed Forces Headquarters in Kuala Lumpur. A week later, the Chief of the Armed Forces Staffs, Tan Sri General Ibrahim Ismail came down to Kuching to get a first hand picture of what had happened and to meet me and my team.

Unknown to me at that time, the CTs in the First and Second Division of Sarawak, under its Director and Political Commissar, Bong Kee Chok, were mulling over the idea of giving up their armed struggle and return to society. This was the result of the relentless pressure from the Security Forces. Bong Kee Chok was further demoralised by the lack of cooperation between factions. Bong Kee Chok wrote a letter to the Chief Minister of Sarawak, Tan Sri Abdul Rahman Yaacob, seeking to negotiate favourable terms for himself and his men. The meeting was held over three days in the residency of Simanggang and was concluded on October 21, 1973 – just ten days after I had attacked their camp in Nonok.

That attack must have been the last straw for him. Subsequently, the town of Simanggang was renamed “Sri Aman” to mark the historical event. That historic operation was the last for me before 3rd Rangers returned to its home base in Taiping in December 1973. I was given the honour to be the parade commander of the Battalion farewell parade. The Chief Minister of Sarawak, Tan Sri Abdul Rahman Yaacob fittingly took the salute. Dressed in camouflage uniforms and wearing the distinctive red mufflers around our necks, a fashion I introduced into Kilat platoon, we braved the rain. It was a resplendent and awesome sight to behold.

It had been a most successful year for the Battalion. Thirty CTs were eliminated – the highest ever achieved by any battalion in a single year. I and Lance Corporal Ahmad Adnan who hails from Johor were awarded the nation’s second highest gallantry award – the Panglima Gagah Berani (PGB). Another soldier, Lance Corporal Peter Bat Wan, a Kenyah from Ulu Batang Rejang in Sarawak, was awarded a Mentioned-In-Despatch. A total of twenty-one soldiers and officers were each awarded a commando knife for having killed at least one CT.

This special award was mooted by Commander 3 Brigade, Brigadier General Hassan Hj Salleh, who knew and understood the importance of appreciating and recognising soldiers’ contribution in the field, especially in war. He learned this from the British Army. In January 1974, 3rd Rangers returned to its home base in Taiping – after a highly successful one year tour of duty in Serian. Kilat platoon was immediately disbanded and the men returned to their respective rifle companies.

It was heartening to note that the Malaysian Army had taken notice of the trend in infantry battalions forming their own special platoons and giving them various names. They saw the successes these elite platoons had achieved. Perhaps, their achievements had influenced the policy makers in the Ministry of Defence into making a decision to officially form a Unit Combat Intelligence Squad (UCIS) in all Infantry battalions. They were considered as an elite platoon in the battalion. In them, the spirit of Kilat platoon lived on.

I and my team were congratulated by the Chief of the Armed Forces Staff,General Tan Sri Ibrahim Ismail accompanied by Lt Col Philip Lee, Maj Gen Dato' Mahmood and Brig Gen Dato' Hassan Hj Salleh. I'm 7th from the left.

I received a Commando Knife from Commander 3 Brigade,

Brig Gen Hassan Hj Salleh for having accounted for the 4th

leader in the leadership heirarchy of 3rd Company NKCP

early in the year.

I received a Commando Knife from Commander 3 Brigade,

Brig Gen Hassan Hj Salleh for having accounted for the 4th

leader in the leadership heirarchy of 3rd Company NKCP

early in the year.

I commanded the Battalion Farewell parade in December 1973,

when our one year tour of duty was over. The CM of Sarawak,

Tan Sri Abdul Rahman Yaacob took the salute. We returned

to our home base in Taiping, Perak.

Operation Jelaku 6 - The Final Blow. Part 2 The Relentless Follow up.

Operation Jelaku 6

The Final Blow

Part 2- The Relentless Follow up.

( to be read with part 1 & 3)

At first light the following day, 8 October, no.12 platoon spearheaded the follow up. I moved some 1000 metres behind, while no. 10 platoon brought up the rear. We moved cautiously following the track that was consistently heading South Easterly towards Sadong river.

On 9 October, Zainil Annuar and his men came across a resting place that showed signs of recent use – most probably an overnight resting place.

As the follow up went into the third day, the tell-tale signs left by the CTs seemed to be getting fresher. Then at about 10 a.m. on October 10, 1973, no. 12 platoon made contact with the rear guards.In the brief exchange of fire, both CTs were killed. It was obvious that the main group was not far away. I studied the map of the area closely and was concerned on the closeness of Sadong river. I knew, if the CTs could reach it before I could get to them, I was quite certain I would lose them for good. Visions of a boat waiting to ferry them across the river played in my mind. Haunted by these possibilities, I decided to go all out to stop them from escaping across the Sadong River.

After giving instruction to Zainil Annuar to make the necessary preparations to winch out the bodies of the two dead CTs out of the operation area, I continued and spearheaded the follow up with my team (my Company Headquarters and members of no. 11 platoon totalling 21 men). By 7 p.m, there was still no contact with the CTs. The traces were now very fresh, indicating they were only a few hours ahead of us.

Darkness was coming in very fast. In the jungle, it came down very much earlier than usual. But, come what may, I had to make a night follow up. We skipped the habitual evening meal, to save an hour or so. Speed and surprise were of utmost importance now.

I decided to go light and left our packs and heavy equipment behind. Six men, enough numbers to fend for themselves, were left to guard our equipments. The night had descended and it made our job trying to follow the track almost impossible.

Under day light, it was easy to see the trampled ground, broken twigs and flattened leaves. In pitch darkness, even with torch lights, it was almost impossible to see these signs. However, the constant South Easterly direction the track had been heading for in the last three days had helped me a great deal to maintain my course.

The damp night air was becoming colder and heavier. Our tired bodies could not generate enough heat to keep us warm. We had been in the swamps for seven days now and our feet were beginning to feel the adverse effect of being soaked in water over long period. Our camouflage uniforms too, were never dry. They were stuck to our bodies like a second skin. To make matters worse, it started to drizzle at about 9 p.m; and as if to add salt to the wound, our torch lights ran out on us. I felt as if I had hit a concrete wall and seemed to have reached a dead end.

I pondered over the situation. Visibility was zero. We couldn’t even see our own hands in front of us. With Sadong river very close - at most 3,000 to 4,000 metres from where I was. The CTs couldn’t be very far away. And with the thought that they could escape across the River was unthinkable. I didn’t want to be haunted for the rest of my life with the failure.

I was in control of the situation and it was up to me whether I wanted success or failure. I decided to push on – regardless of the zero visibility. All was not lost. I still had my magnetic compass to guide me and keep me on the South Easterly direction that the CTs had been steadfastly sticking to.

Mother Nature, too, decided to lend me a helping hand. I saw patches of glowing white lights emitted by certain fungus that grew on rotten leaves and twigs on the jungle floor. Where they were broken by continuous dark break, that was the path the CTs had taken.

We kept on moving, very slowly in tight single file formation to avoid straying away from the group. I peered at my luminous wrist watch. It was almost midnight. Our limbs were numb and we were cold, tired and hungry. Our short rest became more frequent.

Finally, my Company Sergeant Major, Warrant Officer Class 2 Norizan Bakri approached me. “Sir, the men are tired and hungry. Perhaps we should stop for the night. We’ll continue first thing tomorrow morning.” I knew the situation the men were in and perhaps shouldn’t flog a dead horse. On the other hand, we were already so close to the enemy that I just couldn’t give up now and abandoned my effort. Besides, by tomorrow, the enemy could have been safe and sound on the other side of Sadong River. “All right Encik, we will continue for another hour. If nothing comes up by then, we will stop for the night and continue at first light tomorrow morning.” I told my Sergeant Major.

I had to make a compromise. God was on our side. Before that hour was over, my leading scout, Lance Corporal Peter Bat Wan, a Kenyah from Ulu Rejang, whispered to me that he detected the familiar scent of lighted mosquito coils. I didn’t smell anything. So Peter and I went further forward to confirm his finding. He was right. We also saw some faint flickering lights ahead. Torch lights, perhaps. It was with an unbelievable realisation that we, at last, had caught up with the 1st Company of NKCP.

At that instant, the drizzle suddenly turned into a torrential downpour. It was a blessing in disguise for us. It helped drowned the noises we were making and at the same time kept the CTs confined to their tents. I took full advantage of the rain and withdrew some fifty metres back, so that I could plan and deliver my orders.

Based on the intelligence assessment given to me in Serian Camp, I knew the strength of 1st Company NKCP was between sixty to seventy. With only fifteen men, I was numerically outnumbered. However, I had a far superior fire power as every one of us was armed with 5.56mm automatic rifles. The CTs perhaps, had a few automatic weapons. The majority of them were, however, only armed with home-made shot guns.

More importantly was our element of surprise. They knew we were hot on their heels but had never expected we were so determined to even make a night follow up. The scale was therefore heavily tipped in my favour.

...............to be continued in Part 3.

Sunday, 12 October 2008

Operation Jelaku 6 - The Final Blow. Part 1 - The Search and Contact.

That situation was created through the hard works by 3rd Rangers since the beginning of the year (1973). On the very first operation in January 1973, we had started to score, not only in the District of Kuching but in Serian District as well. By May/June 1973, we had eliminated the 3rd Company NKCP operating in the District of Serian and rendered it ineffective as a threat anymore. Thus the only group still largely intact was the 1st Company operating in Kuching and Simanggang District led by Bong Kee Chok. Backed by my track record, I was given a mission to track down and engage this 1st Company NKCP in the inaccessible vast swampy area of Nonok (now Asajaya) where troops had never ventured into.

A satelite picture of Nonok (dark patch). Sadong River

is on the right, South China Sea is to the North. Kuching City

out of the picture to the left.

A satelite picture of Nonok (dark patch). Sadong River

is on the right, South China Sea is to the North. Kuching City

out of the picture to the left.

Operation Jelaku 6 (East of Kuching City)

October 4 – 12, 1973

The Final Blow

Part 1- The Search and Contact

I was promoted to the rank of Captain in July 1973 and knew my days with Kilat platoon had ended. However, I remained the platoon commander for the next four months, until a vacancy was created when Captain Ahmad Rafiee of D Company was posted out of the unit in October. I was immediately available and was appointed by the Commanding Officer, Lt Col Philip Lee Khiu Fui, to command the company.

Young and enthusiastic 25 year old Captain Robert Rizal Abdullah

I left the platoon which I had trained and motivated with a heavy heart but knew and understood I had to progress on in my career. I couldn’t be leading platoons all my life!

Barely a couple of days later, D Company was deployed in the swamps of Nonok (see pic). Having operated there before, I knew conditions there very well. I was there in early January when the monsoon season was at its raging height. And now in October, the monsoon season was just beginning and I didn’t expect the swamps to be as extreme as when I had found it in January.

Based on patterns of sightings of the CTs in the area, it was firmly believed that the 1st Company of NKCP had established a firm base there. I was given its most likely position. Just like James Bond, I was given a mission to seek out and destroy this remaining, elusive and largely intact group. But unlike James Bond, I was not given any sophisticated gadgets, beautiful partners and a self-destruct tape recorder.

On October 4, 1973, my Company was airlifted to a helicopter landing point in the heart of Nonok peninsular, about five to six thousand metres from the target. It was specially constructed by a section of the Royal Engineers for me. No troops had ever ventured that far. The inaccessibility of the swamp had probably given the CTs a false sense of security. What they didn’t know was that no obstacles, however difficult, could hold me back.

To effectively cover my area of responsibility, I broke up my Company into three groups – my company headquarters combined with no. 11 platoon, no. 10 platoon commanded by Sergeant Zakaria and no. 12 platoon commanded by Second Lieutenant Zainil Annuar Ariffin (he later switched to the Military Police Corps and retired as a Major and is now doing well with AIROD).

On 6 October, which happened to be my twenty-fifth birthday, a patrol from no.12 platoon on returning to their base, made a head-on contact with a group of CTs. Thinking they had reached their base, the leading scout had relaxed his guard. And in that split-second indecision, the CT fired first. The leading scout, Ranger Mohd Salleh, was killed instantly. An immediate follow up by Zainil Annuar brought him to an old, large empty camp which could accommodate 60 to 70 CTs.

Early next morning, I met up with Zainil Annuar and his platoon in the CT camp and planned out my next move. Judging by the condition of the camp, it could have been used in excess of five years. It was smack in the middle of the target area given to me.

Except for the discovery of a fresh, well-trodden track that led in a South Easterly direction, we found nothing else of importance. I was absolutely certain the 1st Company of NKCP we were after, was in the camp as recently as one or two days before.

Friday, 10 October 2008

Struck by Lightning

STRUCK BY LIGHNING

(Operation Parabella)

Mention Tanjong Rambutan, Malaysians will envisage the hospital for the mentally impaired patients, located in the God-forsaken place called Tanjong Rambutan, near Ipoh city the capital of Perak state.

In mid 1977, my C Company was deployed in the rugged, rocky and mountainous area of Tanjong Rambutan on a normal search and destroy mission for any Communist Terrorists in the area. As I was to find out the hard way, even the weather was as unpredictable as the patients of Tanjong Rambutans.

For the first few days, I concentrated on the low lands before going up higher and eventually to the top of the rocky and narrow ridges which gave us a fantastic and panoramic view of the land below.

Looking for the CTs were like looking for a needle in the haystack, unless you were given a pin-point accurate intelligence. Otherwise, it was a constant searching and combing the vast jungles of Malaysia, hoping that you would strike a patch of good luck and made a chance encounter with the CTs.

One day, I decided to lay a linear ambush on top of the ridge. By 4 p.m. I started to position the Company in groups of sections (seven to ten men) at intervals of about 100 meters.

At last light (about 6.30 p.m.) during our "stand to" drill, the weather suddenly inclined. It was raining cats and dogs and the strong wind was lashing the trees above and around us. Occasional claps of thunder and lightning strikes had me worried for the safety of my men. My worry was confirmed.

Just as I was about to settle into my hammock, I heard shouts getting closer from the group immediately to my right. A soldier, drenched to the bones, told me that his position was struck by a lightning bolt. Five soldiers who based up underneath a big tree were struck. Lance Corporal Hassan was the most serious. We had to massage and keep him warm the whole night to revive him. That night I radioed a message to my Battalion Headquarters requesting for a medical evacuation the next day.

Early in the morning we packed up and moved along the ridge to look for a suitable point to winch out Lance Corporal Hassan. Syukur alhamdullilah, he was alright. In fact he continued serving in the Rangers and retired as a Warrant Officer Class 1.

Up and away he went. The task was done within a few minutes. Thanks to the RMAF guys who gave us the full cooperation and a job well done.

Up and away he went. The task was done within a few minutes. Thanks to the RMAF guys who gave us the full cooperation and a job well done.

Preparing Lance Corporal Hassan for the winching

Up and away he went. The task was done within a few minutes. Thanks to the RMAF guys who gave us the full cooperation and a job well done.

Up and away he went. The task was done within a few minutes. Thanks to the RMAF guys who gave us the full cooperation and a job well done.

The Wrath

Atop a rugged mountain range.

We strung out in ambush.

And waited for the enemy.

A cobra recoiled, ready to strike.

A spider, waiting for the slightest vibration

to sink its fangs and inject the poison.

Came nightfall, the weather inclined.

Rain poured in torrents wild.

Lightning, flashes blinding.

Thunder claps, deafening.

No sign of abatement,

Our tents our prisons.

Perched high on rocky ground.

Opened to dangers abound.

Cascading waterfalls,

Thunders and fireballs.

I cringed with worry – intuition.

A while later, a shout of exasperation

from the nearest ambush position.

Dismayed that my fear confirmed.

Struck by lightning!

Four soldiers took refuge under a tree.

Three injured slightly, one seriously.

Four claymore mines blown off instantly.

Next day a winching point we looked.

Atop the mountain spooked.

To evacuate the injured soldier

to Base and recover.

Wednesday, 8 October 2008

Operation Beruang 1 (Serian District, Sarawak)

Operation Beruang I

May 22, 1973

(My second success)

By this time, command of the Battalion had

changed hands. Sarawak-born Lt Col philip

Lee Khiu Fui (pic) had taken over from

Lt Col Looi Kum Cheong.

One day, at about 4.00 p.m on May 21, 1973 in Serian camp, while I was conducting a Tang Soo-Do training session with my men, the IO called me into the operations room.

“Unggal! We have an A1 intelligence for you.” The IO’s face was flushed, indicating his excitement. I knew, given the slightest chance, he would swap places with me. However, being a key staff officer, he couldn’t.

“A member of the 3rd Company of the North Kalimantan Communist Party (NKCP) has surrendered yesterday,” he continued. “After a skirmish with B Company a week earlier, the group had dispersed. Now they want to regroup. We know the place. A Special Branch (SB) officer will accompany and guide you there.”

We left camp at 3.00 a.m. and had to reach the CTs’ point of rendezvous before first light. The Special Branch officer accompanied me in my vehicle. About a kilometer from the target, we moved on foot. We reached our target by 6.00 a.m and combed the area. It was deserted. Perhaps we were too early and the CTs had not converged on their meeting place yet. Just when we were beginning to feel disappointed, the Special Branch officer discovered a dead-letter box at the base of a big tree at the rendezvous. It was a regrouping instruction for members of the 3rd Company of North Kalimantan Communist Party.

The instruction was written in Chinese and the SB officer translated the message for us: “Go North-Westerly until you reach a big fallen tree. Knock repeatedly until you hear a reply.” At that point, the SB officer bade us good luck and left the area.

There was no doubt about the presence of CTs in the area. At that moment, they were dispersed in small groups of possibly two or three people and were trying to regroup and form a bigger unit.

I had two courses of action opened to me. Knowing that they would eventually come to the rendezvous, I could lay an ambush and wait for them to come to me. However, as the place was flat and close to villages, the chances of mistaking villagers for CTs were very real. And due to the nature of the ground, we wouldn’t be able to maintain our element of surprise very long. I therefore opted for the second option – check out on the regrouping instruction.

The terrain was mostly covered with secondary vegetations, indicating it had been cultivated at one time or another. There were many tracks, well-used by the locals to go to their farms or into the jungle to find jungle products. As I was to find out later, the CTs would take advantage of this labyrinth of tracks to confuse us and avoid detection.

After about one thousand metres, we came across a big fallen tree. We gave the log a few good knocks and waited for a reply. There was none. We decided to proceed

cautiously along the track. Five minutes later, a familiar shout of “enemy in front” came from the leading scout. A couple of long bursts from his Baretta 5.56 mm automatic rifle shattered the peacefulness and drove a flock of birds from their perch high up on the trees.

I ran forward, just in time to see my two leading scouts scrambled up the steep far bank of a dry river bed. I jumped in after them and found myself stuck knee-deep in the marshy patch on the river bed. I was a sitting duck. The CTs were, however; too busy trying to save their own necks to notice me. I hauled myself out and joined my two scouts at the far bank.

I quickly scanned the place. A pot of boiling porridge, laced with ground nuts and dried anchovies was still cooking over a simmering fire. A few metres away, thrown away in haste, were two bundles of sacks. The CTs hadn’t the time to finish their breakfast as they were caught by total surprise.

“Which way did they run?” I asked Lance Corporal Budun and Ranger Edward Kut.

“That way, sir!” they replied simultaneously, with their outstretched hands pointing to my right. I looked in the direction they were pointing. The thick undergrowth to the right had been trampled and I could hear the CTs bashing their way through the thick undergrowth.

“Let’s go!” I commanded and headed for the trail in hot pursuit. “We must catch them before we lose them in the numerous tracks in the area.”

We moved as fast as we possibly could without compromising our own safety. It was between running and brisk walking. We lost the trails a number of times, when it went through barren patches in the secondary jungle. When that happened, we had to rely on our tracking skills.

After about half an hour, we finally caught up with the CTs in a swamp. They were making splashing sounds as they tried to cross to the safety of the far side. If they could do that, we certainly would lose them. I took a gamble and called them to give up.

“Surrender! Lay down your arms and come out!” I shouted and repeated the call a few more times. I was surprised at the strength of my own voice. They sounded like someone else’s and so out of place. It was a gamble that might work either way. Which ever way it went, I was certain I wouldn’t be the loser. I wanted to give the CTs a chance to come out alive.

With no cover from fire, I felt naked and exposed. My concern was justified. The CTs responded by firing a few bursts from an automatic rifle. The sound was unfamiliar. They must have been using an unfamiliar weapon. We retaliated and returned fire. It was apparent that the CTs were not going to give up without a fight. Without hesitation, we jumped into the swamp. It was surprisingly cold and deep. No wonder the CTs were slow and made a lot of splashing noises. For the first ten metres, the water was up to our chests.

After about thirty metres, we could hear the CTs talking. I lobbed three mini hand grenades in their direction. In the quietness of the jungle, the explosions were thunderous. We crouched low – to avoid being hit by shrapnel. Surprisingly, there was no retaliation. We went for another thirty metres and reached high ground. And there, lying on the ground was Lee Kuen, fourth in the leadership hierarchy of the 3rd Company of NKCP. Judging by the gaping wound on his back, one of the grenades I lobbed had found its target. We went for another few hundred metres to track down the other CTs, but had to give up as it led us to the labyrinth of tracks and populated areas. Endangering civilians must be avoided.

IMPORTANT NOTICE:

I'm trying to re-establish contact with Brig Gen Philip Lee Khiu Fui. If any body knows of his latest address or phone number, please contact me in this blog.

By this time, command of the Battalion had

changed hands. Sarawak-born Lt Col philip

Lee Khiu Fui (pic) had taken over from

Lt Col Looi Kum Cheong.

One day, at about 4.00 p.m on May 21, 1973 in Serian camp, while I was conducting a Tang Soo-Do training session with my men, the IO called me into the operations room.

“Unggal! We have an A1 intelligence for you.” The IO’s face was flushed, indicating his excitement. I knew, given the slightest chance, he would swap places with me. However, being a key staff officer, he couldn’t.

“A member of the 3rd Company of the North Kalimantan Communist Party (NKCP) has surrendered yesterday,” he continued. “After a skirmish with B Company a week earlier, the group had dispersed. Now they want to regroup. We know the place. A Special Branch (SB) officer will accompany and guide you there.”

We left camp at 3.00 a.m. and had to reach the CTs’ point of rendezvous before first light. The Special Branch officer accompanied me in my vehicle. About a kilometer from the target, we moved on foot. We reached our target by 6.00 a.m and combed the area. It was deserted. Perhaps we were too early and the CTs had not converged on their meeting place yet. Just when we were beginning to feel disappointed, the Special Branch officer discovered a dead-letter box at the base of a big tree at the rendezvous. It was a regrouping instruction for members of the 3rd Company of North Kalimantan Communist Party.

The instruction was written in Chinese and the SB officer translated the message for us: “Go North-Westerly until you reach a big fallen tree. Knock repeatedly until you hear a reply.” At that point, the SB officer bade us good luck and left the area.

There was no doubt about the presence of CTs in the area. At that moment, they were dispersed in small groups of possibly two or three people and were trying to regroup and form a bigger unit.

I had two courses of action opened to me. Knowing that they would eventually come to the rendezvous, I could lay an ambush and wait for them to come to me. However, as the place was flat and close to villages, the chances of mistaking villagers for CTs were very real. And due to the nature of the ground, we wouldn’t be able to maintain our element of surprise very long. I therefore opted for the second option – check out on the regrouping instruction.

The terrain was mostly covered with secondary vegetations, indicating it had been cultivated at one time or another. There were many tracks, well-used by the locals to go to their farms or into the jungle to find jungle products. As I was to find out later, the CTs would take advantage of this labyrinth of tracks to confuse us and avoid detection.

After about one thousand metres, we came across a big fallen tree. We gave the log a few good knocks and waited for a reply. There was none. We decided to proceed

cautiously along the track. Five minutes later, a familiar shout of “enemy in front” came from the leading scout. A couple of long bursts from his Baretta 5.56 mm automatic rifle shattered the peacefulness and drove a flock of birds from their perch high up on the trees.

I ran forward, just in time to see my two leading scouts scrambled up the steep far bank of a dry river bed. I jumped in after them and found myself stuck knee-deep in the marshy patch on the river bed. I was a sitting duck. The CTs were, however; too busy trying to save their own necks to notice me. I hauled myself out and joined my two scouts at the far bank.

I quickly scanned the place. A pot of boiling porridge, laced with ground nuts and dried anchovies was still cooking over a simmering fire. A few metres away, thrown away in haste, were two bundles of sacks. The CTs hadn’t the time to finish their breakfast as they were caught by total surprise.

“Which way did they run?” I asked Lance Corporal Budun and Ranger Edward Kut.

“That way, sir!” they replied simultaneously, with their outstretched hands pointing to my right. I looked in the direction they were pointing. The thick undergrowth to the right had been trampled and I could hear the CTs bashing their way through the thick undergrowth.

“Let’s go!” I commanded and headed for the trail in hot pursuit. “We must catch them before we lose them in the numerous tracks in the area.”

We moved as fast as we possibly could without compromising our own safety. It was between running and brisk walking. We lost the trails a number of times, when it went through barren patches in the secondary jungle. When that happened, we had to rely on our tracking skills.

After about half an hour, we finally caught up with the CTs in a swamp. They were making splashing sounds as they tried to cross to the safety of the far side. If they could do that, we certainly would lose them. I took a gamble and called them to give up.

“Surrender! Lay down your arms and come out!” I shouted and repeated the call a few more times. I was surprised at the strength of my own voice. They sounded like someone else’s and so out of place. It was a gamble that might work either way. Which ever way it went, I was certain I wouldn’t be the loser. I wanted to give the CTs a chance to come out alive.

With no cover from fire, I felt naked and exposed. My concern was justified. The CTs responded by firing a few bursts from an automatic rifle. The sound was unfamiliar. They must have been using an unfamiliar weapon. We retaliated and returned fire. It was apparent that the CTs were not going to give up without a fight. Without hesitation, we jumped into the swamp. It was surprisingly cold and deep. No wonder the CTs were slow and made a lot of splashing noises. For the first ten metres, the water was up to our chests.

After about thirty metres, we could hear the CTs talking. I lobbed three mini hand grenades in their direction. In the quietness of the jungle, the explosions were thunderous. We crouched low – to avoid being hit by shrapnel. Surprisingly, there was no retaliation. We went for another thirty metres and reached high ground. And there, lying on the ground was Lee Kuen, fourth in the leadership hierarchy of the 3rd Company of NKCP. Judging by the gaping wound on his back, one of the grenades I lobbed had found its target. We went for another few hundred metres to track down the other CTs, but had to give up as it led us to the labyrinth of tracks and populated areas. Endangering civilians must be avoided.

IMPORTANT NOTICE:

I'm trying to re-establish contact with Brig Gen Philip Lee Khiu Fui. If any body knows of his latest address or phone number, please contact me in this blog.

By this time, command of the Battalion had

changed hands. Sarawak-born Lt Col philip

Lee Khiu Fui (pic) had taken over from

Lt Col Looi Kum Cheong.

By this time, command of the Battalion had

changed hands. Sarawak-born Lt Col philip

Lee Khiu Fui (pic) had taken over from

Lt Col Looi Kum Cheong.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)